She’s slender with a high nose bridge ending in a slight point. Her jaw tapers into a symmetrical v, and her wide doe eyes are framed by double eyelids. According to a public profile written by management, she’s 100 pounds soaking wet. Her height doesn’t matter so much as long as she has enough room between her thighs for another thigh. Her skin should look like glass – pale, glossed, and reflecting the desires projected onto it.

She is any number of kpop stars1 who are trained, trimmed, and tailored to match the “Korean Beauty Standard.” If your ult (your ultimate favorite, in fandom terms) meets enough criteria, she is the nation’s number one beauty. If your ult’s skin is a shade too dark, her eyes too almond, or her hips too wide, well, then she is taking on the oppressive beauty regime, one million streams of her latest single at a time.

Kpop fandom is centered around reaction. The music is secondary to the sales figures especially if they can be used to emphasize your favorite group’s supremacy over others. The worst thing that can happen to an act is being outsold. Talking about a song’s technical structure and contribution to the broader musical landscape is nice, but streams, sales, and how many tickets sold in how few seconds are weapons to wage fan war.

The emphasis on empirical data is not limited to sales figures. Beauty, if international fans are to be believed, is an objective measure in South Korea.

But who defines Korean beauty standards? When King Sejong invented hangul in 1443, did he also write down what the perfect popstar should look like? Despite the frequency at which fans reference the same core set of ideal attributes, there isn’t a source. The Korean idol industry sells fantasy, including the fantasy that they have found the most beautiful women on the face of the earth who have never had beauty augmentations; if anybody had a list of beauty standards, it would be the casting teams choosing what thirteen year old can secure the most endorsement deals before she’s smart enough to hire an attorney and negotiate a decent cut. No such list of standards exists, despite a number of Teen Vogue articles, college papers, and concerned Reddit posts that argue that the pressure to meet them is destroying a generation of teen girls.

The pursuit of beauty has destroyed as many generations of teen girls as there have been generations of teen girls. Every five years our standardized fantasy of a Beautiful Woman replaces herself. In sophomore year of high school, I drove myself to tears a few nights straight because I couldn’t shape a cat eye with my drugstore liquid eyeliner, let alone two that matched. Now, I pay a lady $100 every couple of months to apply various proprietary goops and gels to buff my skin so I can wear as little makeup as possible.

The uncontrollability of nature costs me a couple bucks a month. It costs South Korean women billions2 annually. A toxic mix of inexpensive procedures, competitive job market3, and the latent misogyny of Confucianism has led to $10.7 billion a year’s worth of women changing their faces surgically. South Korea is the plastic surgery capital of the world and Kpop is a walking advertisement.

For young Kpop fans, South Korea seems a paradise full of ethereal, glistening beauties. Once the honeymoon phase wears off, it’s more like the ethereal, glistening beauties of the world simply flock to Seoul in search of one of the few places where you can make money being the cute one in a boyband. Kpop feeds billions of dollars (trillions of won) into the gaping maw4 of the South Korean market: under no circumstances can uggos be a part of that.

The stakes are too high for Korea not to export a small wave of orientalism along with it. This is where those neat little top ten countdown TikToks come in. Fans of Korean pop music may think that sufficient exposure to its popular music may result in a profound, visionary understanding of a society. Going somewhere, maybe chatting up the locals at a pub – forget about it – you don’t even have to know a Korean to understand Koreans. There are entire blogs dedicated to translating the comment section under Korean news articles. What rational person does that? Seeks the wisdom of the freaks [not you, my comment section, you guys are cool] most addicted to their computers that they comment on the news? That does not leave a good impression of a society. But that’s not what fandom orientalism asks fans to do.

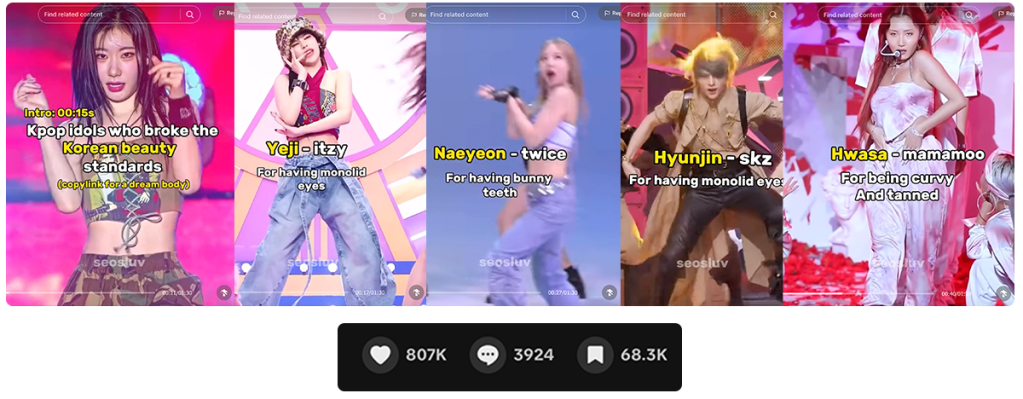

Fandom orientalism here is orientalism stemming from fandom (as opposed to doing orientalism to a fandom, which is what I’m worried you think I might mean but it’s not what I mean) and [insert Kpop fandom names here] are among the worst culprits. Returning to the example of beauty standards: it’s not Koreans with sociology degrees making these perverted5 ranking videos. It’s teenage girls! And it has nasty implications.

One of the more insidious facets of kpop that has leaked into the west is the disturbing prevalence of absurd dieting. It’s an open secret among kpop fans that idols are placed under abusive diet and exercise regimes, yet fans continue to pump out weight loss transformation videos that praise the hard work (of being starved by your manager). While some idols sob through interviews detailing hours of dance practice on nothing but water and apples, others play it up. Some stars do both: on October 11, 2021, mega-star Hyuna posted a photo of her scale reading (not going to tell you the number, but it’s dangerously low), captioned “this is a no-no”; just days later she would share a photo of her measuring her waist (not going to tell you the number, but it’s not the waist of a grown woman).

Despite an effort to restrict pro-ana content on the platform, it doesn’t take much effort to find Tumblr posts instructing readers how to follow their favorite star’s restrictive diets (one particularly infamous diet is as follows: an apple for breakfast, a sweet potato for lunch, and a protein drink for dinner). While Tumblr works on sniffing out creative ways users get around banned tags, TikTok has enabled a new wave of pro-ana kpop content.

As long as there has been an international kpop fandom (that is, since the first Hallyu wave) there have been amateur attempts to understand the Korean mind. How do catchy, gimmicky, and downright insulting-to-the-intelligence songs sell so big? Why are the boys so pretty? How do Koreans themselves understand kpop? These questions aren’t impossible to answer, but teenagers (i.e. those who have the most time on their hands to ponder them) are not so delicate in their approach.

In music-based fandoms, a fan’s duty is to proselytize your idol. You are a source of support for your favorite group, both emotionally and monetarily. To achieve that you buy albums and recommend others stream the latest single. The more recognition, awards, and generalized celebration an idol receives, the more prestige the fans can project onto their community. This is not just true in kpop – Angels have worked their asses off to get Charli an honest-to-god popular album (hi brat summer); Swifties are a more obvious example. What makes kpop special in this case, though, is that kpop fans are fans of a broad category of music. All kpop fans have their favorite member in their favorite group, but are also usually fans of the *gestures hands* whole thing. Meeting international fans outside of fan-specific spaces is less “I like 2NE1 and would die for CL”, but “I like kpop”.

Because international kpop fandoms are feeding into a larger Fandom, there are ample ways to see how artists and trends interact with each other. One of the many ways this manifests is through popular fandom content templates like intergroup friendships, intragroup shipping, best versions of songs, and who wore it best videos.

Through any of these listicle videos do newbies gain two vital pieces of information at once:

- Who are hot people in groups you don’t follow

- Just how hot are they

And because young kpop fans’ relationship to opinion and fact hasn’t unlocked the “it was terrible. I love it” feature, if someone is making a top ten list, it must be true. Beam dozens of these videos directly into your brain as part of a pre-sleep doom scrolling habit, and you start to believe it. Teenagers are not going to interrogate what silly little videos portend for culture at large (and why should they? They are teens), but, boy, can they watch a lot.

Oh, and that’s the thing – the kpop industry is massive. It’s testament to the power of advertising or state planning or both. Over the past 25 years, entertainment has become a vital driver of Korean trade politics. The Hallyu wave not only created more demand for Korean products in Southeast Asia, but has also opened up entirely new markets for things like K-beauty in the U.S. and Europe. This is not a happy side effect but the point. The Korean government has explicitly used culture and art to serve national economic goals and promote a national brand. Every Korean president since Kim Dae-jung has executed a hallyu strategy, spending anywhere from $4.1 million (1994 budget of the “Cultural Industry”) to more money than god (okay, 600 billion-won for a “K-content strategic fund” in 2023) to make it happen.

It would be an exaggeration to say the South Korean government is paying to brainwash our kids but there is a lot of money being spent to create and maintain legions of Koreaboos. The unintended consequences deserve scrutiny. Describing a brief-but-intense social media trend, Steffi Cao writes that fans perceive any lifestyle deficits “through the K-pop industry’s rabbit hole of content—which is often curated and manufactured for exhibition, rather than portraying real lives.” Whether a typical Hollywood press tour would spark “obsessive, betraying signs of disordered eating habits and behaviors” is up in the air, but kpop girl groups certainly do. If you think Wonyoung is the most beautiful woman in the world, you would do anything to look like her too.

- important to note here Kpop idols are not necessarily all Korean – both in 1. An individual might be biracial 2. Some of the biggest stars are not Korean in origin ↩︎

- $10.7 billion for plastic surgery + $14.8 billion for skincare + $12.5 billion for beauty ↩︎

- no, really. This 2018 Stanford blog pins the origin of South Korea’s romance with plastic surgery as a direct result of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. ↩︎

- truly one of the most neoliberal hellscapes of all time. I mean think about it: there is a whole social phenomenon, with its own cute nickname, of women (and other people) getting plastic surgery just to get a regular ass job. Not to get a job as an actress or an idol, but to work at an insurance data analysis firm. That’s a job for ugly people, and ugly people should be allowed to have jobs. ↩︎

- its wrong to rank women ↩︎

Leave a comment